Ruminations – Notes

Track List

The Tavern (1998) – [25:52]

Text: Rumi, (trans. Coleman Barks)

1. Prelude – :45

2. Who Says Words With My Mouth – 3:41

3. A Community of the Spirit – 2:41

4. A Children’s Game – 6:43

5. The Many Wines – 3:15

6. Special Plates – 3:09

7. Burnt Kabob – 3:13

8. The New Rule – 2:19

John Schneider, voice & microtonal guitar

Revised Standards (1987) – [16:17]

(arr. Johnston)

9. REVISED STANDARDS – 6:33

“How Long Has This Been Going On?”, “Little Girl Blue”

10. SET FOR BILLIE HOLIDAY – 7:01

“Lover Man”, “No More”, “When Your Lover Has Gone”

11. I CONCENTRATE ON YOU – 2:28

(Cole Porter, arr. Johnston)

Eclipse String Quartet

Parable (2000) – [25:59]

Text: Rumi, (trans. Coleman Barks)

12. Prologue – 3:17

13. A Mouse & a Frog – 5:32

14. The Long String – 11:31

15. The Force of Friendship – 8:52

Karen Clark/voice, Jim Sullivan/clarinet, Sarah Thornblade/violin

16. Bonus Track: Johnston on ‘The Tavern’ — 7:20

Notes

The three works recorded on this CD form a fascinating  complement to the existing discography of Ben Johnston’s music in presenting pieces from what may be called his “late period”. The earliest works recorded here (for string quartet) date from 1987, a few years after his retirement from teaching at the University of Illinois; the other two date from 1998 (The Tavern) and 2000 (Parable), the latter being one of the last works he has completed. Whether or not this “late period” signals a significant change of style or of manner must remain an open question until the music he composed in the late 1980s and 1990s becomes better known. What is immediately striking about the works collected here is how they revisit afresh two issues that have concerned Johnston throughout his career: an engagement with popular music, and a deep concern with spiritual questions as they have been understood in religious and mystical traditions worldwide. If one may perhaps sense a God-and-the-Devil dichotomy in the subject matter of these three works, it might be said that the music itself tells a different story. The themes of love (fulfilled or rejected, sacred or profane), of drunkenness and sobriety, of existential questions and religious ones (“All day I think about it, then at night I say it. / Where did I come from, and what am I supposed to be doing?” asks The Tavern; “sometimes when we beings come together Christ becomes visible”, declares Parable) – all these themes are unified by Johnston’s use of a “new” tuning system, extended just intonation, with its ability to reconcile, symbolically at least, seeming opposites.

complement to the existing discography of Ben Johnston’s music in presenting pieces from what may be called his “late period”. The earliest works recorded here (for string quartet) date from 1987, a few years after his retirement from teaching at the University of Illinois; the other two date from 1998 (The Tavern) and 2000 (Parable), the latter being one of the last works he has completed. Whether or not this “late period” signals a significant change of style or of manner must remain an open question until the music he composed in the late 1980s and 1990s becomes better known. What is immediately striking about the works collected here is how they revisit afresh two issues that have concerned Johnston throughout his career: an engagement with popular music, and a deep concern with spiritual questions as they have been understood in religious and mystical traditions worldwide. If one may perhaps sense a God-and-the-Devil dichotomy in the subject matter of these three works, it might be said that the music itself tells a different story. The themes of love (fulfilled or rejected, sacred or profane), of drunkenness and sobriety, of existential questions and religious ones (“All day I think about it, then at night I say it. / Where did I come from, and what am I supposed to be doing?” asks The Tavern; “sometimes when we beings come together Christ becomes visible”, declares Parable) – all these themes are unified by Johnston’s use of a “new” tuning system, extended just intonation, with its ability to reconcile, symbolically at least, seeming opposites.

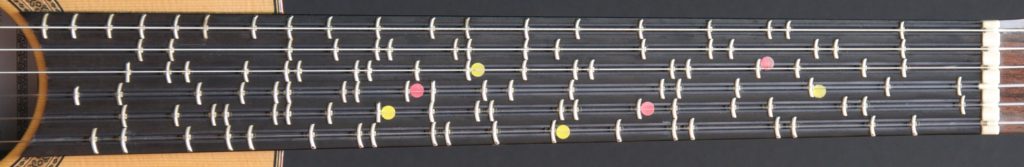

Just intonation is of course not a “new” system at all, but is a manner of tuning that stretches back to the ancient civilizations of China, Greece and elsewhere. But its use in western music diminished with the introduction of keyboards with their fixed, rather than flexible, intonation. The work of pioneers in the twentieth century, chief among them Johnson’s mentor and friend Harry Partch (1901-74), reopened the door closed by systems of temperament – “those twelve black and white bars in front of musical freedom”, as Partch memorably described the predominant western system of twelve-note equal temperament. Johnston’s practice extends that of Partch in exploring more complex harmonic relationships still based on the use of pure intervals, as found in the natural vibrations of a string or a column of air. His use of what he (quite correctly, from a historical vantage point) calls “extended just intonation” gives him the ability to compose along a broad spectrum – from simple, “normal”-sounding harmonies, through extended but still familiar jazz harmonies, to wholly unfamiliar harmonies that push into new and unchartered territory, providing material that twenty-first-century music will surely want to understand.

Johnston’s use of extended just intonation has sometimes led him to reconceive familiar idioms in his own terms, a process that might be thought of as a kind of musical revisionism. Revised Standards, Set for Billie Holiday, and I Concentrate on You are examples. The nature of Johnston’s recasting of familiar jazz standards is quite distinct from the ironic, detached use of elements of jazz in the music of Stravinsky; it is perhaps closer to the unselfconscious usage of jazz and Latin popular idioms by his teacher Darius Milhaud. These versions of tunes by George Gershwin, Richard Rodgers, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter and others, for string quartet, reconceive the vocabulary of jazz harmony in terms of extended just intonation. The familiar “blues seventh” here is not the minor seventh of tempered tuning, but an interval about a third of a semitone lower, more precisely described by the frequency ratio 7/4. Its sonority, not just its mathematics, is quite different – less restless for resolution, more settled, more sensuous. And the occasional use of intervals derived from higher partials of the harmonic series, such as eleven and thirteen, give a radically new flavor to the rich harmonies characteristic of this era of jazz history. (It should be remembered that this music was in Johnston’s blood from an early age: he grew up in Macon, Georgia, listening to records of Duke Ellington and Jimmie Lunceford; and during his military service he briefly considered a career as a dance-band arranger. Some of us are grateful that he subsequently took a different path.)

Johnston’s life has been marked by a profound interest in, and varying forms of devotion to, religious belief. Viewed as a whole, his trajectory has been partly ecumenical, with a period of intense involvement in Roman Catholicism, and partly what might be termed a form of “interfaith pluralism”, involving the study of traditional religions such as Buddhism and mystical systems such as that of Gurdjieff. Johnston has long maintained that, “[p]roperly understood, art and religion have the same aims… [a] search inward: an effort to bring each surface life into meaningful relation with its most personal, least egocentric level of self”. His underlying motivation, regardless of its outward manifestation, has been the wish to transcend our obsession with the individual ego, to subordinate our selfish humanity to the search for a greater good, a greater sense of belonging. The two song cycles recorded here, The Tavern, for voice and microtonal guitar, and Parable for voice, violin and clarinet, both set verses by the thirteenth-century Persian poet, mystic and theologian Rumi (Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī), in translations by the American poet Coleman Barks. (Although noted for his involvement with Persian literature, Barks does not speak or read the language, so his “translations” are, technically speaking, paraphrases.) Rumi’s texts pose situations or quests of a significance that often transcend his time and place, and have influenced poetic traditions across Asia and (in translation) in modern America.

Johnston’s two cycles take somewhat different approaches to vocal style. In Parable the settings are, vocally speaking, more traditional, recitative-like, whereas in The Tavern he specifically wanted a quasi-spoken, “intoning” approach to the texts, following the example of Partch, to keep their meaning as clear as possible for the audience. In the performances on this disc every word is audible. (His approach in The Tavern was inspired by Johnston’s hearing dedicatee John Schneider’s performance of Partch’s Barstow.) The meanings of the poems, complex and multi-dimensional as they often are, are further heightened by the music. The full range of symbolism inherent in Johnston’s system of just intonation, in which certain intervals are often typically linked in his mind with particular emotional states – the eleventh partial associated with the ambiguity between opposites, the thirteenth with death or a sense of existential foreboding – is deployed here, analogously perhaps to forms of word-painting in more traditional repertory. On a more immediately audible level, the eleventh and thirteenth partials were deployed in these works to mirror the presence of the quartertone intervals of Middle Eastern music. Yet despite the ingenuity of the compositional craft, there is in both cycles a sense of artlessness, a wish to make technique serve the goal of greater expressivity and communication. In a letter to the present author in 1993, Johnston remarked: “I think I have always known how to speak to people in my music. If it was not widely known when it was written (or rather soon after) I think it is due principally to the tyranny of the ‘new music’ scene in which composers write and play for each other. I have never let that attitude permeate my work except on a very temporary basis.” These late works join with earlier phases of Johnston’s compositional output in substantiating that claim, and enrich our understanding of the achievement of one of America’s finest creative voices.

Bob Gilmore, Amsterdam, October 2013

Editor of Ben Johnston: Maximum Clarity and other writings on music (U. of Illinois Press, 2006), ASCAP Deems Taylor Award

The Tavern

(1998)

The Tavern is a setting of Coleman Barth’s translation of Rumi. It’s a Sufi idea of what it is to come as a beginner to that particular brand of spiritual discipline and how, in one aspect, it is a lot like getting drunk in a tavern. In other words, to paraphrase Rumi, it’s necessary to have that intoxicating element there, which is both a tremendous source of energy and a danger. The danger is obvious, especially in the Muslim tradition, since drinking is out – that’s not done. It’s definitely on the wrong side. So, what we’re talking about there is a metaphor, but at the same time the metaphor is out. We’re talking about something which is psychologically not safe. But, on the other hand, it is necessary – and the reason it is necessary is that there has to be a dissolving of the ordinary ego. When you do that, what are you going to put in its place? It is a little bit like drunkenness. It’s not that simple, but the sacrifice you have to make is nothing short of organizing and re-organizing your entire life. I’d say getting into any spiritual discipline is going to be like that. I remember a conversation with John Cage where I asked him what he thought of the Sufi tradition and he said, “I like dry wine. That’s sweet wine.”

We set out to do The Tavern as a collaboration, because John Schneider knows the guitar as very few (maybe not any) know it. I was long ago convinced that the fingerboard, which is removable and based on deciding upon a set of pitches needed for each particular tuning, ought if possible to become the next step in the history of the guitar in performance. Our work to make The Tavern is a major step toward this goal.

I bring to our collaboration a concept of pitch organization based on pure, simple pitch ratios like those used by Harry Partch, but freed from the limitations imposed by his instrumental designs. As he knew, and agreed to from our earliest contact onward, our ways of using these fresh tuning possibilities imply, and in practice produce, very different kinds of music, but with common roots. I am a very different kind of artist from Harry Partch, but what matters most is the results of each approach. Let’s let our musics speak for themselves. A major figure in this peace-making is John Schneider. We must be careful to see this role as liberating —- not as a breaking of tradition. Tradition?? Harry Partch?? What a self-contradiction! The question is not “How do we keep it going?” It is, “Where do we go from here?” – Ben Johnston (Nov 2009)

I bring to our collaboration a concept of pitch organization based on pure, simple pitch ratios like those used by Harry Partch, but freed from the limitations imposed by his instrumental designs. As he knew, and agreed to from our earliest contact onward, our ways of using these fresh tuning possibilities imply, and in practice produce, very different kinds of music, but with common roots. I am a very different kind of artist from Harry Partch, but what matters most is the results of each approach. Let’s let our musics speak for themselves. A major figure in this peace-making is John Schneider. We must be careful to see this role as liberating —- not as a breaking of tradition. Tradition?? Harry Partch?? What a self-contradiction! The question is not “How do we keep it going?” It is, “Where do we go from here?” – Ben Johnston (Nov 2009)

REVISED STANDARDS

(1987)

In the seventies I did some jazz improvisation with a small, female string group who liked my way of handling jazz harmony. We focused on jazz standards, but found ourselves at least equally challenged and moved by working on tunes composed to feature particular female singers such as Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald.

In a jazz improvisation, the soloist has very great freedom to play with intonation, while his back-up group maintains a comparatively strict accompaniment as a steadying but challenging factor. Harmony is richly altered from tradition in most jazz, but it does not typically play with tuning as a soloist does. In my just-tuned jazz, spontaneity is disciplined in a new way so that all players are creating both melodic and harmonic microtonal innovation that can vary greatly in how it affects the listener, but always innovates in both melody and harmony. Both freedom and strictness are asked of the whole ensemble. And the richness of an infinite variety of pitches and rhythms is held together as a byproduct of extended just intonation.

I leave to the listener the adventure of relating the words behind these instrumental pieces by getting to know their original sources, and making comparisons to these revised standards. – Ben Johnston

Parable

(2000)

The nature of a parable is to cause each person being given the parable to form his own intuition of its meaning. This parable has a Sufi origin. Since there are almost as many kinds of Sufi as there are Christian religious sects this is not much help pinning down its symbolic meaning. I am composing this at my desk on Easter morning: yet another red herring. This parable concerns a manatee—a sea-cow— seeking a meaningful integrated life on shore. Can this be? And if it is, what does it tell us about spiritual aims?

The nature of a parable is to cause each person being given the parable to form his own intuition of its meaning. This parable has a Sufi origin. Since there are almost as many kinds of Sufi as there are Christian religious sects this is not much help pinning down its symbolic meaning. I am composing this at my desk on Easter morning: yet another red herring. This parable concerns a manatee—a sea-cow— seeking a meaningful integrated life on shore. Can this be? And if it is, what does it tell us about spiritual aims?

I composed this work for Dora Ohrenstein to follow up on her recording of Calamity Jane to her Daughter [Urban Diva CRI 654]. – Ben Johnston

This excerpt from a 3-hour conversation was recorded in San Francisco the day previous to the premiere of The Tavern at Other Minds [OM 14, 2009].

Artists

John Schneider is a Grammy® nominated guitarist, composer,  author and broadcaster, whose weekly television and radio programs have brought the sound of the guitar into millions of homes. Called “A delight,” by the New York Times and a “Microtonalist maven,” by the Wall Street Journal, Fanfare declared, “Schneider creates elegant dynamic levels and layers on his solo guitar, and he always projects the poetry of the music.” He has performed in Europe, Japan, Vietnam & throughout North America, and been featured by New Music America, the DaCamera Society, Southwest Chamber Music, New American Music Festival, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony and the BBC. He is the founding artistic director of MicroFest, Partch, and can be heard weekly on Pacifica Radio’s The Global Village [KPFK 90.7-fm in Los Angeles & worldwide at www.kpfk.org]. Having recorded for Bridge, Cambria, Etcetera, Innova, Mode, New Albion, and Pitch Records, his most recent release is Harry Partch’s Bitter Music (Bridge Records, 2011).

author and broadcaster, whose weekly television and radio programs have brought the sound of the guitar into millions of homes. Called “A delight,” by the New York Times and a “Microtonalist maven,” by the Wall Street Journal, Fanfare declared, “Schneider creates elegant dynamic levels and layers on his solo guitar, and he always projects the poetry of the music.” He has performed in Europe, Japan, Vietnam & throughout North America, and been featured by New Music America, the DaCamera Society, Southwest Chamber Music, New American Music Festival, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony and the BBC. He is the founding artistic director of MicroFest, Partch, and can be heard weekly on Pacifica Radio’s The Global Village [KPFK 90.7-fm in Los Angeles & worldwide at www.kpfk.org]. Having recorded for Bridge, Cambria, Etcetera, Innova, Mode, New Albion, and Pitch Records, his most recent release is Harry Partch’s Bitter Music (Bridge Records, 2011).

The Eclipse Quartet is dedicated to the music of twentieth century and present day composers. The scope of their repertoire spans works from John Cage and Morton Subotnick to collaborations with the singers Beck and Caetano Veloso. Eclipse has the versatility to cross genres from works that include electronics and computer processing to the jazz compositions of Grammy® award winning pianist Billy Childs. The Quartet has performed frequently on both coasts, and has participated in festivals such as the Look and Listen Festival in NYC, Festival for New American Music in Sacramento, Scarlatti Festival (Naples, Italy), Martha’s Vineyard Chamber Music Festival, Angel City Jazz Festival and MicroFest, and have been Artists in Residence at Mills College in Oakland California and at the historic artists’ retreat Villa Aurora in Los Angeles. Eclipse can also be heard on the Bridge, New World, and Tzadik record labels.

The Eclipse Quartet is dedicated to the music of twentieth century and present day composers. The scope of their repertoire spans works from John Cage and Morton Subotnick to collaborations with the singers Beck and Caetano Veloso. Eclipse has the versatility to cross genres from works that include electronics and computer processing to the jazz compositions of Grammy® award winning pianist Billy Childs. The Quartet has performed frequently on both coasts, and has participated in festivals such as the Look and Listen Festival in NYC, Festival for New American Music in Sacramento, Scarlatti Festival (Naples, Italy), Martha’s Vineyard Chamber Music Festival, Angel City Jazz Festival and MicroFest, and have been Artists in Residence at Mills College in Oakland California and at the historic artists’ retreat Villa Aurora in Los Angeles. Eclipse can also be heard on the Bridge, New World, and Tzadik record labels.

Karen Clark’s repertory spans the centuries to  include world premieres of medieval passions and modern works by living composers, and poets, such as, Gary Snyder, Joseph Schwantner, Ben Johnston, and Fred Frith. New York Times critics have praised Karen Clark’s “warm, rich mezzo,” commending her “astonishing range of expressive subtlety,” and acclaiming her “among the glories,” “one of the loveliest voices,” and “the most striking.” Karen’s 2012 recording, On Cold Mountain: Songs on Poems of Gary Snyder (Innova) with the Galax Quartet received accolades from the San Francisco Chronicle who called her singing “majestic.” And, her singing of the premiere of Ben Johnston’s Parable, prompted the L.A. Times to write: “Karen Clark brought a rich intensity to the stories. The performance was stunning.” Karen Clark lives in Northern California.

include world premieres of medieval passions and modern works by living composers, and poets, such as, Gary Snyder, Joseph Schwantner, Ben Johnston, and Fred Frith. New York Times critics have praised Karen Clark’s “warm, rich mezzo,” commending her “astonishing range of expressive subtlety,” and acclaiming her “among the glories,” “one of the loveliest voices,” and “the most striking.” Karen’s 2012 recording, On Cold Mountain: Songs on Poems of Gary Snyder (Innova) with the Galax Quartet received accolades from the San Francisco Chronicle who called her singing “majestic.” And, her singing of the premiere of Ben Johnston’s Parable, prompted the L.A. Times to write: “Karen Clark brought a rich intensity to the stories. The performance was stunning.” Karen Clark lives in Northern California.

Jim Sullivan explores the versatility of the clarinet, bass clarinet and contrabass clarinet in an expansive range of styles and repertoire. Based in Los Angeles, he honed his microtonal skills studying maqam while playing for a decade with classical Arabic ensemble Kan Zaman. Having worked extensively with composer Andrew McIntosh, he recorded Symmetry Etudes,

Jim Sullivan explores the versatility of the clarinet, bass clarinet and contrabass clarinet in an expansive range of styles and repertoire. Based in Los Angeles, he honed his microtonal skills studying maqam while playing for a decade with classical Arabic ensemble Kan Zaman. Having worked extensively with composer Andrew McIntosh, he recorded Symmetry Etudes,  a series of pieces written in just intonation (2013), performing excerpts with the LA Phil New Music Group. Additionally, he has performed music from Harry Partch’s Oedipus with the Partch ensemble, where he became “intimate” friends with the Chromelodeon.

a series of pieces written in just intonation (2013), performing excerpts with the LA Phil New Music Group. Additionally, he has performed music from Harry Partch’s Oedipus with the Partch ensemble, where he became “intimate” friends with the Chromelodeon.

Sarah Thornblade is the associate principal second violin of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. The Los Angeles Times describes her playing as “rapturously winning” and the Santa Barbara News writes that she is a “marvelously versatile violinist.” An avid chamber musician, Sarah is a member of both the Eclipse Quartet and Xtet, ensembles dedicated to performing 20th century and contemporary music. Eclipse is a visiting artist at Mills College. Recent premiers by the quartet include works by Peter Garland, Chico Mello, Stephen Cohn and Zeena Parkins. Sarah is on the faculty of Pomona College and is also an active recording musician for film and television. She holds degrees from Indiana University and Northern Illinois University and studied with Miriam Fried, Mathias Tacke and Shmuel Ashkenasi.

Special Thanks: Charles Amirkahnian [Other Minds] for arranging the premiere of The Tavern & Paul Berkolds for singing it, Patrick Scott [Jacaranda] for presenting the premiere of Revised Standards, & Royer Labs for the extra R122-V to record it.

Recording

The Tavern, recorded April 5, 2009 & Oct. 23, 2010 – Studio 34, Los Angeles: engineer, John Schneider

Revised Standards, recorded November 11, 2012 – Architecture, Los Angeles: engineer, Scott Fraser

Parable, recorded June 26, 2012 – Architecture, Los Angeles: engineer, Scott Fraser

Ben Johnston Interview, recorded March 4, 2009 – San Francisco: engineer, John Schneider

Producer: John Schneider

Recording Engineers: Scott Fraser, John Schneider

Editing: John Schneider

Mastering: Scott Fraser Architecture

Liner Notes: Bob Gilmore & Ben Johnston

Publishers: all music by Smith Publications, Vermont

Photographs:

Cover – ‘Lotto’ Carpet (Islamic, late 16th century) – Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Ben Johnston at Djerassi & Johnston/Schneider at Other Minds 14, John Fago ©2009 All rights reserved

Ben Johnston at KUSC: Photo by Jon Roy. ©2013 All rights reserved

Eclipse: photo by Sally J. Coates

John Schneider: photo by Robert Hale

Karen Clark: photo by Norbert Brein-Kozakewycz

Sarah Thornblade & James Sullivan at Architecture: photo by John Schneider

℗©2014 MicroFest Records, all rights reserved