Just Strings Notes

Track List

Five Athabascan Dances (1995) – [12:58] – John Luther Adams

1. Grandpa Joe’s Traveling Song – 1:59

2. They Will All Go – 1:26

3. Deenaadai’ – 3:23

4. Grandpa Joe’s Hunting Song – 2:03

5. Potlach Song of a Lonely man – 4:07

Harp Suite #1 – [14:08] – Lou Harrison

6. Jahla (1972) – 1:55

7. Music for Bill & Me (1967) – 5:04

8. Avalokiteshvara (1964) – 2:10

9. Sonata in Ishartum (1977) – 1:49

10. Serenado (1952) – 2:04

11. Beverly’s Troubadour Piece (1967) – 1:36

12. Lyric Phrases (1972) – [3:22] – Lou Harrison

Harp Suite #2 – [16:12] – Lou Harrison

13. A Little Gamelon (1951) – 2:06

14. Palace Music (1971) – 3:14

15. Little Homage to Eratosthenes (1974) – 1:46

16. Threnody to the Memory of Oliver Daniel (1990/1992) – 3:50

17-19. Three Dances from Faust (1985) I. 1:24 II. 1:39 III. 2:14 – 5:15

Five Yup’ik Dances (1995) – [10:06] – John Luther Adams

20. Invitation to the Dance – 1:58

21. Jump Rope Song – 2:07

22. Shaman’s Moon Song – 1:50

23. Juggling Song – 2:08

24. It Circles Me – 2:03

25. In Honor of the Divine Mr. Handel (1991) – [6:28] – Lou Harrison

Just Strings

Alison Bjorkedal – Harps

John Schneider – Guitars

T.J. Troy – Percussion

Notes

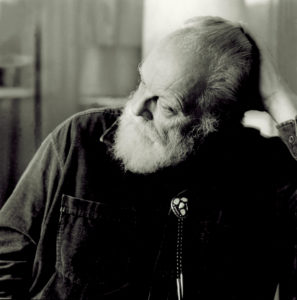

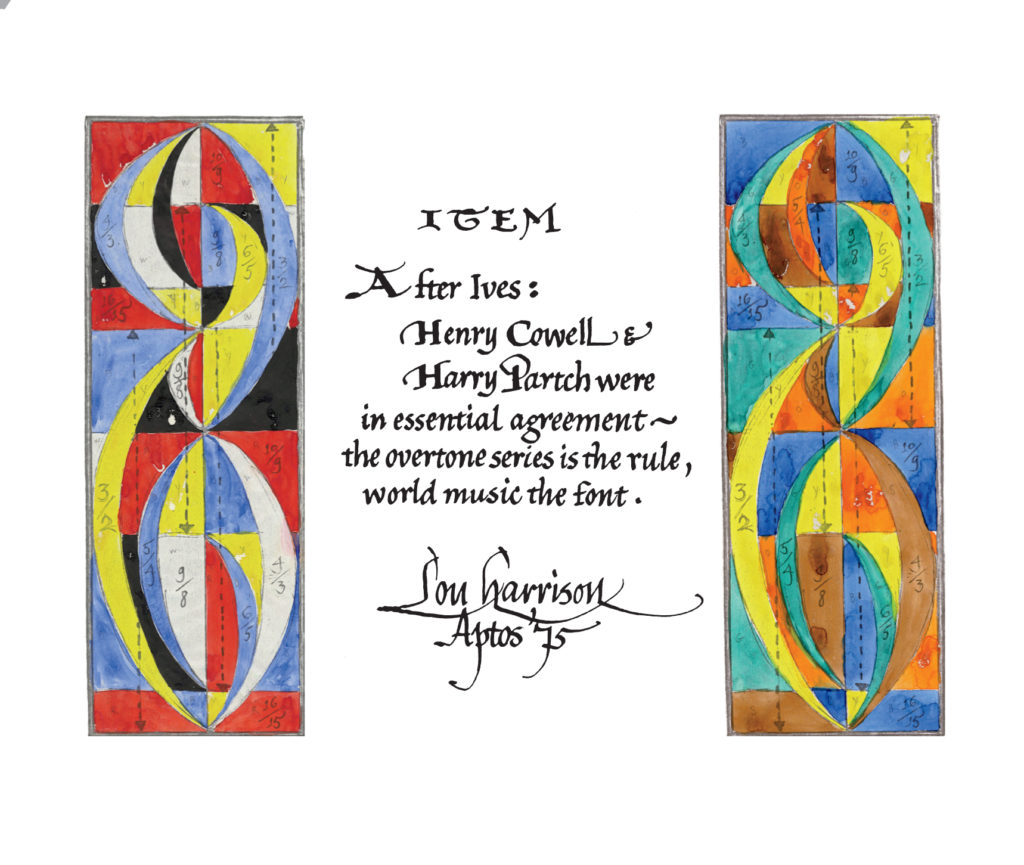

The parallels between Lou Harrison and John Luther Adams, as distinct as their differences, help to define a deep and sparkling tributary of American music and art, one profoundly connected to the land and culture of the American West and (in all its meanings) the Pacific. More than a generation apart, Harrison and Adams both first found their inspiration and education on the West Coast, departed in search of their careers, and only then realized that the place they belonged, personally and artistically, was embedded within the natural world. In the 1930s and early 40s, Harrison studied with American new music pioneer Henry Cowell in San Francisco and Viennese master Arnold Schoenberg in Los Angeles, helping create, along with his friend John Cage, a vibrant California arts scene of percussion music, modern dance, and experimental theater. He moved to New York in 1943 but managed only a decade within its unforgiving noise and pressure. He retreated to a cabin overlooking the ocean near Santa Cruz, California, where his music transformed from earlier thickets of atonal counterpoint to radiant melodies that absorbed the riches from the other side of the Pacific.

Harrison’s relocation to the quiet fern-covered forests cleansed his ears, eased his mind, and refreshed his compositional outlook. He fell in love with the crystalline sounds of tunings based on the natural harmonics of string instruments, known as just intonation (from which Just Strings gets its name) and mostly abandoned the industrial conveniences of tempered scales otherwise electronically enshrined by professional tuners on every living room piano.

Harrison’s relocation to the quiet fern-covered forests cleansed his ears, eased his mind, and refreshed his compositional outlook. He fell in love with the crystalline sounds of tunings based on the natural harmonics of string instruments, known as just intonation (from which Just Strings gets its name) and mostly abandoned the industrial conveniences of tempered scales otherwise electronically enshrined by professional tuners on every living room piano.

One of his favorite instruments to experiment with tunings was the harp, whose strings could be more readily tuned than the piano or harpsichord. “I have always been ‘exceedingly enamored’ of the harp,” he wrote to John Schneider of Just Strings, “and approve of a quote from the 16th- and 17th-century Spanish that Zabeleta wrote about—‘A Gentleman will not be for long without his harp.’ Indeed, what you are doing with guitar and harp brings vividly to mind the manuscript pictures of the court of Alfonso the Wise, especially since those instruments were then properly tuned.”

In the 1960s, Harrison bought his own Lyon and Healy diatonic harp. For that instrument, smaller and more intimate than the concert harp, he composed his 1972 Jahla in the Form of a Ductia to Pleasure Leopold Stokowski on his Ninetieth Birthday in honor of the famous conductor, who was also a champion of Harrison’s works. Typically for Harrison, he conflated the European form of a ductia, a medieval dance in which repeated phrase ending melodies tie together a sequence of melodies, with the Indian form of a jhala, in which propulsive drone pitches are interpolated between notes of the melody.

Harrison wrote his touching Music for Bill and Me in 1967, the year he met his life partner Bill Colvig, and made it simple enough that two novice harpers could play together. Sometimes Harrison would adapt previous plucked string works for harp, as with his Avalokiteshvara, originally written for psaltery, a kind of zither based on the Chinese zheng. This life-giving dance is named for the Buddhist bodhisattva of careful listening—he hears the cries of and helps the suffering.

Along with his interest in Buddhism, Harrison in the 1970s was fascinated with the work of University of California Berkeley scholar Anne Kilmer, who had just deciphered nearly 4000-year-old Sumerian clay tablets that described tunings from this remote time. Sonata in Ishartum adopts the Sumerian name for this ancient diatonic mode and tuning.

Harrison wrote Serenado (the title is the Esperanto version of Serenade) on learning that his friend composer Frank Wigglesworth had taken up the guitar, suggesting that it would sound best on a guitar refretted to just intonation. Until he was able to procure such an unusual instrument, Harrison adapted the charming work for harp and often incorporated it into suites, such as this one, sometimes played by his friend and fellow harpist Beverly Bellows. At a 1967 party celebrating the recent purchase of his small “troubadour” harp, Harrison wrote an impromptu Beverly’s Troubadour Piece for Bellows. Like Avalokiteshvara, it is an energetic but barline-less dance accompanied by sparkling percussion ostinatos.

In 1971, as Harrison was completing his puppet opera Young Caesar, he reconnected with Pauline Benton, a specialist in the Chinese art of shadow puppetry, whose performances Harrison had first seen in the 1930s at Mills College in Oakland. Harrison and Benton resurrected this theater company for a few performances, which rekindled Harrison’s love of the form, also famous in Indonesia. Prompted by Betty Polus’ book on shadow puppetry and perhaps visions of future performances, Harrison wrote his Lyric Phrases in the form of a “kit,” that is, a series of melodic fragments that can be repeated and recombined in any order to be determined by the performer. Harrison’s mentor Henry Cowell had invented this flexible system of composing, and Harrison extended the flexibility to the mode (also left up to the performer) and the presence, or absence, of a drone and percussion ostinato. The piece can therefore sound significantly different in other performances, but for this one, John Schneider has chosen an unusual tuning of the diatonic Lydian mode, playing it on the re-fretted just intonation Reso-phonic guitar that Harrison created for his last composition, Scenes from Nek Chand (2002). The Lyric Phrases lay in one of Harrison’s dozens of notebooks until it was discovered after his death— this is its first recording.

Like the Serenado, Harrison’s Little Gamelon dates from the years just before his move back West, when he was reconnecting with nature in bucolic North Carolina, at the revolutionary and influential art school Black Mountain College. There he collaborated with choreographer Katherine Litz and wrote this piece (originally for piano) for her dance class. A charming trifle, it prefigures both his masterful Suite for Violin, Piano and Small Orchestra and his love affair with the real gamelan orchestra of Java a couple of decades later.

Music of the East also inspired Harrison’s rarely heard puppet opera Young Caesar. It nevertheless includes some of his most beguiling music, including Palace Music, originally for psaltery. In this scene, the teenaged (soon to be) Julius Caesar, a soldier from the powerful West, walks in wonder through the sumptuous palace of Nicomedes, king of Bythinia in Asia Minor and representative of the beauties of the East. A poignant non-diatonic mode, characteristic of the Near East, mirrors this colorful splendor and contrasts with the diatonic modes of the scenes in Rome.

A devotee of classical civilizations, Harrison wrote Little Homage to Eratosthenes on the just intonation scale invented by the third century BCE scholar and librarian of the famed library of Alexandria. This work for wire-strung harp and gongs laid apparently unperformed in Harrison’s notebooks, and this is its first recording.

Harrison wrote many pieces to honor people, both living and departed, who were important to his life. Oliver Daniel was a fierce supporter of new American music and Harrison’s in particular, in his roles as administrator for American Composers Alliance, Composers Recordings Inc., and other organizations. The day after learning of his death in 1990, Harrison wrote Threnody to the Memory of Oliver Daniel in a mournful mode of Alexandrian polymath Claudius Ptolemy’s distinctive “soft diatonic” tuning.

In 1985, Harrison’s ambition to create puppet dramas was still not quenched, and he collaborated with University of California Santa Cruz puppeteer Kathy Foley to create a modern tragi-comedy version of Goethe’s Faust, but in the style of an Indonesian wayang puppet drama. The score consisted of works for both gamelan and Western orchestras, but the music for Western instruments is mostly unperformed. This is the first recording of the Three Dances for Harp from that production.

In Honor of the Divine Mr. Handel was originally part of a large suite Harrison composed to honor the radio station KPFA in Berkeley at the inauguration of its new facilities in 1991. One of the musicians in Harrison’s gamelan, Henry Spiller, was also an accomplished harpist, and so Harrison decided to write a piece for him that quotes the famous harp concerto of one of Harrison’s favorite composers, George Frederic Handel (conventionally known by the English as “the divine Mr. Handel”) but with the accompaniment of a Javanese gamelan. Harrison fashioned a delightful homage that incorporates both the Baroque concerto grosso form and the sparkling metallophones of this Asian orchestra, even with this decidedly non-European just intonation tuning.

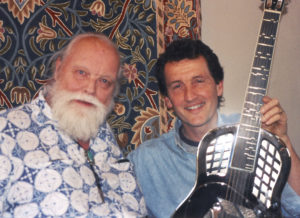

Like Harrison, John Luther Adams also found an inspiring education in California, at the newly opened and free-spirited California Institute of the Arts. The year he graduated, 1973, having won a composition award from a jury that included Harrison, Adams took the bus up the coast to meet the elder composer, who would become a role model and friend. Later, when considering whether to devote himself full time to music or keep a part time job, Adams sought the advice of his mentor. “There are no half-time jobs, John,” Harrison advised, “only half- time salaries.” Adams promptly quit his job and never looked back.

Like Harrison, John Luther Adams also found an inspiring education in California, at the newly opened and free-spirited California Institute of the Arts. The year he graduated, 1973, having won a composition award from a jury that included Harrison, Adams took the bus up the coast to meet the elder composer, who would become a role model and friend. Later, when considering whether to devote himself full time to music or keep a part time job, Adams sought the advice of his mentor. “There are no half-time jobs, John,” Harrison advised, “only half- time salaries.” Adams promptly quit his job and never looked back.

After some uncertainty and wandering (echoing Harrison’s East Coast period), Adams ended up in Alaska, realizing that he had finally found his home. “I was under the spell of these vast, seemingly empty landscapes, the tundra, or the frozen Yukon river delta,” he told the San Francisco Classical Voice. “I was also just completely taken with Alaska and Barnett Newman and color field painting—art in which there’s apparently nothing but that seems to resonate so deeply. I wanted to do something like that in music, take everything out, remove all the lines, and have these floating fields of musical color.”

Like Harrison, Adams found a cabin surrounded by wilderness, this one without running water and only a wood-fired stove for heat. “Here on the northern extreme of the continent,” he told Musicworks, “I’m much more directly influenced by the rich cultural traditions of the indigenous peoples, and by the overwhelming presence of the place itself.”

His indigenous friends helped introduce him to the cultures of the region, and in 1995, when the Interlink Festival and the U.S. Embassy in Japan commissioned him for a work for the Just Strings ensemble, he drew upon traditional songs of the Gwich’in (also known as Athabascan) people for his Five Athabascan Dances. “Traditional Athabascan songs are sung in unison, with no harmony or counterpoint,” he said. “Working as a composer in the Western tradition, I have extended and transformed these Athabascan melodies in many ways. In the process, they have become something else, somewhat far removed from Alaska Native music in sound and in context.The first and fourth pieces are based on songs by Joe Beetus, a Koyukon elder from the village of Huslia. The second is based on a traditional farewell song of the Dena’ina people, as remembered by Peter Kalifornsky and transcribed by Thomas F. Johnston. The principal melody of the third piece is derived from my setting of a poem by Adeline Peter Raboff, in her native Gwich’in language. The final piece ‘Potlatch Song of a Lonely Man’ is based on the song by the late Peter Kalifornsky, the last speaker of the Dena’ina language. These Athabascan Dances are dedicated, with respect, to the first peoples of the Northern Interior and the Kenai Peninsula.” Just Strings premiered the work at Tokyo’s Casals Hall in 1995.

Adams paired those pieces with Five Yup’ik Dances, based on the songs of the First People of the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta. Like most of Harrison’s harp pieces, these pieces are all diatonic, that is, with no accidentals. Adams remembered, “After looking through the score Lou was very enthusiastic, saying: ‘You’ve rediscovered those seven tones as something wild, fresh, and new.’ Encouraged by Lou’s reaction, I went on to compose Dream In White On White—a larger work in Pythagorean diatonic tuning which led eventually to the 75-minute expanse of In the White Silence.”

Of these dances, he wrote, “The principal melodies of the first, third, and fifth pieces are traditionally sung in unison by a group of drummers, to accompany ecstatic and hypnotic dancing. The second and fourth pieces are based on game songs for jumping rope and juggling pebbles.The melodies of the first four pieces are drawn from the collection Yup’ik Eskimo Songs, compiled by Thomas F. Johnston and Tupou L. Pulu and published by the University of Alaska. The fifth I learned from Yup’ik singer and dancer Chuna McIntyre. I have varied these sources in many ways, adding ostinato figurations, countermelodies, introductions, interludes and codas. The Five Yup’ik Dances are dedicated to the memory of Thomas F. Johnston, whose work on behalf of Alaska Native music has enriched the lives of people of all cultures. They are part of a larger cycle inspired by the music of Alaska’s indigenous peoples. It is my hope that these pieces convey something of my deep admiration and respect for Native cultures, and my love for the forests, rivers, lakes, mountains, glaciers, seascapes and tundra of Alaska.”

In 1988, Adams arranged for an Alaskan residency for Harrison, who arrived with Bill Colvig and a small gamelan. Harrison, with his California constitution, faced the cold with forbearance but warmly encouraged Adams. “Lou observed that by choosing to live in Alaska I had chosen to develop a deep relationship with place and to avoid what he called ‘the group chattering of the metropolis,’” said Adams. Indeed, both composers’ distance from the chattering metropolis nurtured music of luminous expanses and timelessness. After Harrison’s death in 2003, Adams composed an hour-long orchestral tribute, For Lou Harrison, and quoted John Cage’s poem honoring Harrison for the title of his 2014 Pulitzer Prize-winning Become Ocean. Adams’s own poetic remembrance on Harrison’s death is perhaps the most touching of these honors:

The great redwood has fallen.

Light streams into the forest.

The sound will reverberate

for generations to come.

Just intonation is a method of tuning, rather than a particular scale, where frequencies are related by relatively simple integer ratios. The pitches that result are therefore quite different from those of standard equal temperament, which is based on irrational frequency relationships. Although listeners need not be aware of this acoustical arithmetic in order to appreciate the sweet harmonies that result, here are the details of the scales used in this recording:

Athabascan Dances and Yup’ik Dances :: (“Pythagorean” or Ditone tuning) C—1/1, 2187/2048, 9/8, 32/27, 81/64, 4/3, 729/512, 3/2, 27/16, 16/9, 243/128

Jahla :: C—1/1, 9/8, 5/4, 4/3, 3/2, 5/3, 15/8

Music for Bill & Me :: A—1/1, 9/8, 6/5, 4/3, 3/2, 27/16, 9/5

Avalokiteshvara :: A—1/1, 9/8, 5/4, 27/20, 3/2, 27/16

Sonata in Ishartum :: A—1/1, 9/8, 32/27, 4/3, 3/2, 128/81, 16/9

Serenado :: from G—1/1, 9/8, 5/4, 4/3, 3/2, 5/3 15/8

Beverly’s Troubadour Piece :: A—1/1, 9/8, 6/5, 4/3, 3/2, 9/5

Lyric Phrases :: C—1/1, 8/7, 9/7, 10/7, 32/21, 12/7, 40/21

A Little Gamelon :: C—1/1, 5/4, 4/3, 3/2, 15/8

Palace Music :: C#—1/1, 10/9, 6/5, 4/3, 25/18, 5/3, 16/9, 2/1

Eratosthenes’ Chromatic :: E—1/1, 20/19, 10/9, 4/3, 3/2, 30/19, 5/3

Threnody :: E—1/1, 21/20, 7/6, 4/3, 3/2, 63/40, 7/4

Three Dances from Faust :: A—1/1, 9/8, 6/5, 5/4, 4/3, 3/2, 8/5, 5/3, 9/5

In Honor of the Divine Mr. Handel :: C—1/1, 35/32, 5/4, 21/16, 105/64, 7/4

— Bill Alves co-author, Lou Harrison biography (forthcoming, U. of Indiana Press)

The Artists

JUST STRINGS is a unique ensemble that specializes in the performance of music in just intonation. Since its formation in 1991 to perform the music of Lou Harrison and Harry Partch, the ensemble has gone on to commission and premiere works by John Luther Adams, Sasha Bogdanowitsch, Mamoru Fujieda, Larry Polansky, James Tenney, and others. They per- formed throughout Japan under the auspices of the American Embassy’s prestigious Interlink Festival, as well as Chamber Music in Historic Sites, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, UCLA’s Partch Centennial Celebration, Sacramento’s Festival of New American Music, Minnesota Public Radio’s American Mavericks, the Songlines series at Mills College, MicroFest, and the Getty Center. Their CD Just West Coast was CD Review’s “CD of the Year” in 1994 and inducted into Fanfare’s “Classical Hall of Fame,” while other recordings include Sasha Matson’s The Fifth Lake (New Albion Records), Just Guitars (Bridge Records), and the all-Lou Harrison album Por Gitaro (Mode Records).

JOHN SCHNEIDER is the Grammy winning guitarist, composer, author, and broadcaster whose weekly television and radio programs have brought the sound of the guitar into millions of homes. He holds a Ph.D. in Physics & Music from University College Cardiff (Wales), music degrees from the University of California, the Royal College of Music (London), and is President Emeritus of the Guitar Foundation of America. A specialist in contemporary music, Schneider’s The Contemporary Guitar has become the standard text in the field. Called “A delight” by the New York Times and a “Microtonalist maven” by the Wall Street Journal, Fanfare declared, “Schneider creates elegant dynamic levels and layers on his solo guitar, and he always projects the poetry of the music.” He has performed in Europe, Japan, Vietnam & throughout North America, and been featured by New Music America, the DaCamera Society, Southwest Chamber Music, New American Music Festival, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Other Minds, and the BBC. He is the founding artistic director of MicroFest, PARTCH, and can be heard weekly on Pacifica Radio’s The Global Village (www.kpfk.org). His recordings can be found on Bridge, Cambria, Etcetera, Innova, MicroFest, Mode, New Albion, and Pitch record labels. (www.JohnSchneider.LA).

JOHN SCHNEIDER is the Grammy winning guitarist, composer, author, and broadcaster whose weekly television and radio programs have brought the sound of the guitar into millions of homes. He holds a Ph.D. in Physics & Music from University College Cardiff (Wales), music degrees from the University of California, the Royal College of Music (London), and is President Emeritus of the Guitar Foundation of America. A specialist in contemporary music, Schneider’s The Contemporary Guitar has become the standard text in the field. Called “A delight” by the New York Times and a “Microtonalist maven” by the Wall Street Journal, Fanfare declared, “Schneider creates elegant dynamic levels and layers on his solo guitar, and he always projects the poetry of the music.” He has performed in Europe, Japan, Vietnam & throughout North America, and been featured by New Music America, the DaCamera Society, Southwest Chamber Music, New American Music Festival, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Other Minds, and the BBC. He is the founding artistic director of MicroFest, PARTCH, and can be heard weekly on Pacifica Radio’s The Global Village (www.kpfk.org). His recordings can be found on Bridge, Cambria, Etcetera, Innova, MicroFest, Mode, New Albion, and Pitch record labels. (www.JohnSchneider.LA).

ALISON BJORKEDAL is a Grammy winning harpist and established orchestral, opera, chamber, and recording musician (San Diego, Pasadena, & Long Beach Symphonies, L.A. Opera, Long Beach Opera, Southwest Chamber Music, MUSE/IQUE, Golden State Pops Orchestra), as well as a passionate educator. A sought-after interpreter of contemporary music, her world premieres include William Kraft’s Encounters XII for harp and percussion, Wadada Leo Smith’s Ten Freedom Summers, and U.S. premieres of works by Unsuk Chin, Anne LeBaron, Lou Harrison, Ton That Thiet, Nguyen Thien Dao, and Ga- briela Ortiz. In addition to the harp, Alison also plays the 72-string Kithara with the multiple Grammy Award nominated ensemble PARTCH. (www.alisonbjorkedal.com)

ALISON BJORKEDAL is a Grammy winning harpist and established orchestral, opera, chamber, and recording musician (San Diego, Pasadena, & Long Beach Symphonies, L.A. Opera, Long Beach Opera, Southwest Chamber Music, MUSE/IQUE, Golden State Pops Orchestra), as well as a passionate educator. A sought-after interpreter of contemporary music, her world premieres include William Kraft’s Encounters XII for harp and percussion, Wadada Leo Smith’s Ten Freedom Summers, and U.S. premieres of works by Unsuk Chin, Anne LeBaron, Lou Harrison, Ton That Thiet, Nguyen Thien Dao, and Ga- briela Ortiz. In addition to the harp, Alison also plays the 72-string Kithara with the multiple Grammy Award nominated ensemble PARTCH. (www.alisonbjorkedal.com)

Grammy winner T.J. TROY combines an eclectic knowledge of percussion from around the world with his innate musicality to create a distinct and powerful voice in modern music. He has appeared in some of the most prestigious festivals of traditional and contemporary music worldwide, performing with PARTCH, MESTO, Ustad Aashish Khan, Mamak Khadem, Omar Faruk Tekbilek, Karima Skalli, Adam Rudolph, and Cirque du Soleil, and was a featured performer/lecturer at the 2015 Seattle World Rhythm Festival. An award-winning composer, T.J.’s music comes to life through his ensemble, Run Downhill, cross-contextualizing Americana/folk music, comic book art and narrative, and multi-media live performance; his revolutionary SPURS #1 album/motion comic was an official selection at the Seattle Transmedia and Independent Film Festival (STIFF 2015). (www.tjtroy.com)

Grammy winner T.J. TROY combines an eclectic knowledge of percussion from around the world with his innate musicality to create a distinct and powerful voice in modern music. He has appeared in some of the most prestigious festivals of traditional and contemporary music worldwide, performing with PARTCH, MESTO, Ustad Aashish Khan, Mamak Khadem, Omar Faruk Tekbilek, Karima Skalli, Adam Rudolph, and Cirque du Soleil, and was a featured performer/lecturer at the 2015 Seattle World Rhythm Festival. An award-winning composer, T.J.’s music comes to life through his ensemble, Run Downhill, cross-contextualizing Americana/folk music, comic book art and narrative, and multi-media live performance; his revolutionary SPURS #1 album/motion comic was an official selection at the Seattle Transmedia and Independent Film Festival (STIFF 2015). (www.tjtroy.com)

The Harvey Mudd College American Gamelan is an ensemble of instruments led by composer Bill Alves, that plays new works outside of the tradition of the classical Javanese orchestra. While these pieces may be informed by traditional Javanese works, the composers have adapted this ensemble for their own expression, a “tradition” established in the United States by Lou Harrison and Bill Colvig, who named their ensembles “American Gamelan.” However, unlike their homemade instruments, these were built on commission by Suhirdjan of Yogyakarta, Java. Nevertheless, they are unusual for Javanese instruments in several ways. Even though their tuning falls into the traditional categories known as pelog (a seven-note scale) and slendro (a five-note scale), they are tuned to particular just intonation versions of those scales.

Harps :: Lyon & Healy Style 30, Dusty Strings Crescendo 34, Triplett wire-strung

Guitars :: Vogt Fine-Tuneable Guitar (1988), National “Harmonic” Guitar (2003)

Publishers :: Harp Suite #1, Salvi Harp Corp. Athabascan & Yup’ik Dances, Taiga Press

Recording

Harp Suites, recorded July 25/26, 2014 Architecture, Los Angeles: engineer, Scott Fraser

Athabascan & Yup’ik Dances, Lyric Phrases, recorded September 12/13, 2014 Architecture, Los Angeles: engineer, Scott Fraser

In Honor of the Divine Mr. Handel, recorded April 26, 2014 Drinkward Recital Hall, Claremont: engineer, John Schneider

Producer: John Schneider

Recording Engineers: Scott Frasier, John Schneider

Editing: John Schneider

Mastering Engineer: Scott Fraser, Architecture

Liner Notes: Bill Alves

Design: Erin Schneider

Photographs :: John Luther Adams, Lou Harrison, Bill Colvig :: photos by Dennis Keeley

Just Strings at Architecture :: photo by Scott Fraser

Tuning Diagrams by Lou Harrison, used by permission

Harrison Item used by permission of C.F. Peters Corp.

This recording was funded in part through a grant from the Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc.

℗©2015 MicroFest Records, all rights reserved

P.O. Box 237, Pasadena, CA 91102