Just National Guitar – Notes

Track List

Scenes from Nek Chand Lou Harrison (8:58)

|1| The Leading Lady

|2| The Rock Garden

|3| The Sinuous Arcade

Tombo Por Lou John Schneider (12:25)

|4| Plaint

|5| Passacaglia

|6| Valse Triste

|7| Jahla

|8| The Day Before Peter Yates (1:19)

Quando Cosas Malas Caen Del Cielo Terry Riley (11:26)

|9| National Broadstreet March

|10| Quando Cosas Malas caen Del Cielo

|11| Man’s Best Friend Peter Yates (1:47)

Rational Melodies Tom Johnson (9:41)

|12| I.

|13| II.

|14| III.

|15| IV.

|16| V.

|17| XV.

|18| XVI.

|19| 17-23 Peter Yates (1:25)

|20| Almost Square Carter Scholz (7:28)

|21| Is Is Peter Yates (3:25)

Suite for National Guitar Lou Harrison (16:58)

|22| Jahla

|23| Solo

|24| Air

|25| Serenado por Gitaro

|26| Music for Bill & Me

|27| Jahla in the form of a Ductia

|28| Is That It Peter Yates (2:07)

TOTAL: 66:33

About the Artist

John Schneider is the Grammy winning guitarist, composer, author, and broadcaster whose weekly television and radio programs have brought the sound of the guitar into millions of homes. He holds a Ph.D. in Physics & Music from University College Cardiff (U.K.), music degrees from the University of California, the Royal College of Music (London), and is President Emeritus of the Guitar Foundation of America. A specialist in contemporary music, Schneider’s The Contemporary Guitar has become the standard text in the field.

John Schneider is the Grammy winning guitarist, composer, author, and broadcaster whose weekly television and radio programs have brought the sound of the guitar into millions of homes. He holds a Ph.D. in Physics & Music from University College Cardiff (U.K.), music degrees from the University of California, the Royal College of Music (London), and is President Emeritus of the Guitar Foundation of America. A specialist in contemporary music, Schneider’s The Contemporary Guitar has become the standard text in the field.

Called “A delight” by the New York Times and a “Microtonalist maven” by the Wall Street Journal, Fanfare declared, “Schneider creates elegant dynamic levels and layers on his solo guitar, and he always projects the poetry of the music.” He has performed in Europe, Japan, Vietnam, China, throughout North America, and been featuredby New Music America, the DaCamera Society, Southwest Chamber Music, New American Music Festival, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Other Minds, and the BBC.

He is the founding artistic director of MicroFest, PARTCH, MicroFest Records, and can be heard weekly on Pacifica Radio’s The Global Village (www.kpfk.org). His recordings can be found on Bridge, Cambria, Etcetera, Innova, MicroFest, Mode, New Albion, and Pitch record labels.

Notes

It all started when Lou Harrison was commissioned to write a guitar piece for the 2002 Other Minds Festival. It turned out, however, that he was not interested in the nylon strung classical guitar, but instead, longed to hear strings of metal:

While mother played an afternoon of Mah Jong with friends, we children listened to records or the radio. We heard a lot of Hawaiian music and I can remember the sliding and waving guitar tones over a gap of almost eighty years. The wonderful sculpture and architecture of Nek Chand, near Chandigarh set me to composing three small pieces in admiration. (program notes from the premiere)

And thus, Scenes from Nek Chand was born. With the help of the dedicatee David Tanenbaum, the search for the ‘right’ guitar sound led the composer to the National Resophonic Tricone guitar. It was the right sound all right, but not quite the right notes, as Harrison’s previous five decade commitment to pure tunings had led him to demand the pure intervals of Just Intonation instead of what he called the “industrial gray of equal temperament.” He had also recently discovered a new scale:

For years now, I’ve been writing in 6-tone modes – I don’t know why, but its fun – so I made the discovery, for an idiot like me, that overtones 6 through 12 constitute nature’s own 6-tone mode. I was astonished to realize that this 6-tone mode is nature’s only mode that is continuous in the overtone series – there’s no 7-tone that works, and nothing else does – only a 6-tone mode works. It’s fascinating! But that’s after many years of inventing six-tone modes, I suddenly realized that nature’s own is between 6 & 12, and its beautiful too…!” (personal interview, 2002)

In 2002, the first Just National guitar was made, though not in time for the premiere. When I commissioned the instrument, however, it seemed rather limiting to produce an instrument with only the six notes that Lou had specified, so with the help of Terry Riley, Lou’s assistant Bill Slye, and Harrison biographer/composer Bill Alves, we created a 12-note scale based on the overtones of the notes D and G:

And the result has proven to be an inspiration for many composers since.

One of my assistants tells me that other people are taking it up, and this is sort of a minor industry happening. I’m amazed at what they have been developing out of it, and delighted. (radio interview, 2002)

National Resophonic’s Don Young was so enthusiastic about the project that he made an extra instrument as a ‘loaner’ to be sent to prospective customers and composers. The results have been astonishing: since its creation, there are now over two dozen works for the instrument, and the list is growing yearly. Some of the first works to be written for it are found here on this album, as well as works by Larry Polansky, David Doty, Walter Zimmerman, and Ezequiel Menalled recorded by Elliot Simpson on The Wayward Trail (MicroFest Records M•F 6). And so, the adventure continues…

Scenes from Nek Chand (2002)

For most of his professional life, Lou Harrison had been considered outside the world of ‘Classical Music’ because of his interest in non-Western traditions and his emphasis on melodic & harmonic simplicity in a century seemingly dominated by complexity and dissonance. He had long been interested in so-called Outsider Art in the visual and poetic arts as well, subscribing in his last years to an English journal called Raw Vision that celebrates this unique byway of the creative world. It was there that he encountered the extraordinary work of Indian artist Nek Chand, whose homemade sculptures and their surrounding “Rock Garden” had recently become one of India’s most popular architectural achievements.

Begun in the mid 1960’s as a clandestine garden carved out of the jungle beyond the modern city of Chandigarh, Nek Chand began decorating his tiny oasis with statues built of recycled detritus. It soon grew to several acres with interlinking courtyards peopled by hundreds of his fantastic mosaic sculptures. Upon discovery, the sanctuary was initially threatened with demolition, but the local government eventually supported his efforts with labor and funding so that now, the Rock Garden of Chandigarh contains several thousand sculptures on over twenty-five acres of land which include huge buildings, waterfalls, and walled paths, hosting over 5,000 visitors daily.

As somebody pointed out in an essay, since Picasso, there’s been no ‘top’ artist, as it were, and Nek Chand meets all the criteria! Outside of Chandigarh, he has acres filled with sculpture that he’s made by himself – this is all ‘outsider’ stuff. He started out by carrying pieces of concrete on a bicycle…there are some absolutely lovely things. One, I can’t remember what it’s called, but it’s a sloping hill, and its all tiled-on geometrically, Gaudi style, you know. On it are standing figures like the uncovered warriors of China – there are hundreds of them – except they are further apart in Chand’s work.

That’s only one of them: the Leaning Lady is a single slab and she leans like that (holds hand at an angle), and it’s just beautiful. In Raw Vision there are pictures of them. A stream goes through the property and he’s built an arcade, literally, following the shore. It’s very big – there are sizeable arches made of bags of concrete piled up, but they’re real arches. It’s two sided, that is to say there are arches, and then a roof so you can promenade on the top with bannisters. In every arch there is an iron-chained swing for two people…it’s just beautiful.” (personal interview, 2002)

And so, an artistic ‘outsider’ inspired a musical maverick, a term recently been coined to describe composers outside the musical mainstream, thanks in part to Michael Tilson Thomas’ celebrated “American Mavericks” concert/radio series with the San Francisco Symphony:

A maverick composer is an outsider…you know the Art people have made categories for this…I think MTT is using ‘maverick’ as outsider artists…none of us, really, took commissions until very late. Actually what happens is the Outsiders become the Classicists of the next period, as Debussy said…I still think of myself as a maverick artist; well, my newest work – it demands a new kind of instrument, & a new kind of tuning, and a new kind of technique – it’s the Scenes From Nek Chand…”. (www.musicmavericks.org)

Though the opening “The Leaning Lady” features the gliding tones so common to the Hawaiian music of Harrison’s youth, I have chosen to use slide ornaments much more common with Hindustani slide guitar style, in deference to the nationality of the work’s inspiration. My 2003 premiere recording of the work was directly from the manuscript that Harrison sent me. But, unbeknownst to me, he had added some bass notes to “The Rock Garden” movement, which I happily include here.

(Note: I played the Scenes for Lou in the Grand Hall of his last ‘composition’ – the Straw Bale House in the high desert of Joshua Tree. He was particularly proud of the collar ties for the high barrel vaulted ceiling that he said could easily bear the weight of a swing – an activity that he eagerly anticipated. Whenever I play the The Sinous Arcade With Swings in the Arches, I can’t help but imagine that sweet pendulation.)

Tombo por Lou (2006) by John Schneider

This musical ‘tombstone’ marks the passing of the divine Mr. Harrison in a manner reminiscent of the lute or harpsichord tombeaux of the French Baroque, and was written specifically for the refretted National Steel Guitar, an instrument of his own invention.

The initial keening of the Plaint is followed by the repetitions of a descending Passacaglia (with nods to both Purcell & Harrison’s teacher Schoenberg), which itself begins to descend as the movement progresses. The grieving gradually subsides with the Valse Triste, whose bittersweet harmonies remind us that the dance of life continues in spite of loss, while the spritely Jahla varies a theme from Harrison’s lovely Music Primer and is resplendent with the energetic inertia of Harrison’s final decades, only to be cut short, mid-leap, as was the composer’s life. The final measures are in keeping with the onomatopoetic images of several 17th century predecessors that represented, for example, a soul’s upward journey towards heaven with a final ascending scale, or the infamous descending scale which—rather than condemn the deceased to eternal damnation—simply described one composer’s ultimate corporeal demise that was caused by the artist unintentionally descending a staircase, headfirst.

Tombo por Lou was written on the chilly Northern Coast of California with the title to Guy Madden’s 2003 film The Saddest Music in the World constantly in my thoughts. The title is in Esperanto, one of Harrison’s many passions. — J.S.

Five Quips (2007) by Peter Yates

“Five Quips set to music remarks by five cherished commentators on the human experience – Oscar Levant, Groucho Marx, Mark Twain, George Orwell and Franz Kafka. The manuscript incorporates a technique pioneered by 16th-century singer-players in which notes to be sung and notes to be played are presented on the same staff, but in different colors. This resulted in a score that looked cool and was efficient in its use of space, but also required extra dedication for its realization, for which the composer is thankful to the performer. The piece was inspired by John Schneider’s artistry and courage in bringing to fruition, across years of inquiry, a deep and wide range of welcome musical exploration.” — P. Y.

Quando Cosas Malas Caen del Cielo (2003) by Terry Riley

“On March 19, 2003, I was anxiously listening to radio station KPFA as news came in of the commencement of operation ‘Shock and Awe.’ As ‘Bush the lesser’ unleashed the American killing machines on the people of Iraq, I felt inspired to join a small group of war protestors in Nevada City, California, including legendary musician/activist Utah Phillips. There was a protest march down Broad Street and at the end we sat down in civil disobedience…the police asked us to leave and we didn’t, so were arrested. As punishment the judge let me do community service. I worked it out so that my community service was to write a piece of music. What resulted was National Broad Street March and Quando Cosas Malas Caen del Cielo…movements of a suite for the National Steel Guitar with a tuning designed by Lou Harrison.” — T.R.

7 Rational Melodies (1982) by Tom Johnson

“Rationality, or more precisely, deductive logic, has seldom been the controlling factor in musical composition. Composers are usually more interested in inspiration, intuition, feelings, self-expression. Lately, however, there has been a tendency for composers to give up individual control over every note, and rely on factors outside themselves. Pieces have been controlled by the wind, by chance, by the idiosyncrasies of tape recorders, or by unpredictable variations in electronic circuitry, for example, and it seems to me that composing by adherence to logical premises involves a similar way of thinking.

I got interested in writing Rational Melodies because I liked music that made sense; music that I could explain. I had an instinct for symmetry and clarity and I wanted to write music that people could understand, music that at least I could understand. So I could say, ‘this has to be F# because if it were F natural it wouldn’t be logical with what happened just before and it must always be a major second,’ or whatever the logic was. So I started, around 1979-80, to write these particular Rational Melodies. To make sure that I understood what I was doing, and that other people could also understand what I was doing, I wrote explanatory notes for each melody. I ended up with 21, and they are all different.

I. A 37-note rhythm (the 7-bar pattern) revolves around a 6-note melody. Six into 37 leaves a remainder of one, so we shift to a new starting note each time around.

II. The “dragon” pattern, as explained in visual terms in several of Martin Gardner’s Scientific American columns in 1967 provides the basic sequence here.

III. Many minimalist composers have developed their music by adding or subtracting notes, one at a time…Here the notes are added and subtracted in such a way that we rotate around five pitches: 1 12 123 1234 12345 2345 345 45 5…

IV. The melody moves around a cycle of seven notes first following the rhythm note-rest note-rest, then note-note-rest note-note-rest, then note-note-note-rest note-note-note-rest, etc.

V. The sequence here hardly requires clarification but I should comment on the scale. As in many Rational Melodies, the scale here is a regular alternation of two intervals, in this case major 3rds and major 2nds. This is a compromise between completely regular 1-interval scales, such as the chromatic or whole-tone scales, which can become tedious to listen to, and those irregular sequences of intervals such as one finds in major or dorian, which carry strong emotional connotations and often seem to distract from the logical sequences themselves.

XV. Rational Melody No.15 is a 15-note layered melody using five pitches. Thus we can begin with our complete melody, and make a gradual transition to a double-time version of the same melody, without changing tempo and without changing any of the original notes.

XVI. This is another doubling process: special rules are used for inserting new notes between each pair of existing notes in order to make the melody twice as long:

Several curious things occur as side effects of this logic. The second half of the pattern always ends up as the reverse of the first half.” — T.J.

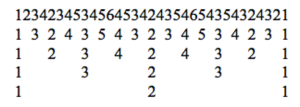

Almost Square (2005) by Carter Scholz

While each of Tom Johnson’s Rational Melodies has its own singular logic/process, Carter Scholz goes one step further. He gives us a rationally expanding melody with its own charming logic, accompanied by a purposefully asymmetric accompaniment made up of repeating segments of the original, each in a different length, creating a kind of limping triple canon. He tells us,

Almost Square is for a trio of melody instruments with optional soloist. It is based on the algebraic relation (n+1)·(n–1)=n2–1. That is, take any number n, add one to it, subtract one from it, multiply these two numbers, and the result is almost equal to n squared – just one less. The title nods to the algebraic form, but it’s also a wish that the thing will swing.

In Almost Square, the solo part consists of 13 sequential melodic building blocks, each inhabiting its own measure that is exactly one beat longer than the one that precedes it. They are revealed to us in a very special order: 1, 1-2-1, 1-2-3-2-1, 1-2-3-4-3-2-1…and so on, with each cycle punctuated by 3 beats of silence. When the longest sequence of 1à13à1 is reached, the additive process reverses direction and becomes subtractive [1à11à1, 1à10à1, 1à9à1, 1à8à1…], thus our expanding universe begins to contract until we reach the beginning again. A palindrome!

1-2-1

1-2-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-11-10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-11-12-11-10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-11-10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-6-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-5-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-4-3-2-1

1-2-3-2-1

1-2-1

But that’s just the Solo voice. The accompaniment, which was written first, follows its own inexorable logic: a trio of voices uses the same building blocks as the soloist and in the same sequence, but each voice repeats only one of the melodies per cycle. For example, the solo cycle 1à7à1 that takes 49 beats is accompanied by the soprano part playing the 8/4 melody 6 times (48 beats), while the alto plays the 7/4 melody 7 times (49 beats), and the tenor the 6/4 melody 8 times (48 beats). Doesn’t quite square, does it? hence the title. And since each of the accompanying melodies is of a different length, they never harmonize with one another in exactly the same way, creating a progressively revolving harmony that temporarily links with the solo line as it goes sailing by, either in unison, or canonically:

If your eyes are crossing at the math and the logic that gave birth to this jewel-like marvel, close them, and let your ears be your guide. The counterpoint is delightful, the shift of meters enticing, and the composer is right—it swings.

Suite for National Steel (1952-89)

Jahla

Solo

Air

Serenado por Gitaro

Music for Bill & Me

Jahla in the form of a Ductia

Once the Just National had been invented, I couldn’t help but wonder which of Lou’s other pieces would work well on it. Having had a long history of arranging and recording his music for refretted classic guitar, we discussed many pieces. The Serenade (1978)? He shook his head, “Absolutely not…” as the pure sevenths on the National were way too flat for that mode. Serenado por Gitaro (1952), his first piece for justly fretted guitar? Yes! in fact he preferred it on the new instrument, and so on.

The opening Jahla is the final movement from the curious Pedal Sonata (1989) for solo organ. As mentioned in his Music Primer, “JAHLAS are very useful. The tone (or tones) of the drone are rhythmically reiterated between all tones of the melody in ‘Perpetuum mobile’ style.” Contrary to most drones, however, Harrison specifies “melody tones legato, drone tones staccato.”

Solo (1972) was written for the set of Tenor Bells that are part of Harrison’s newly created American Gamelan. The score includes this proviso: NB: The tuning must be “Just” D Major, otherwise the tension of the “false B Minor” will be lost, & the “narrow escape” (tonally) in the climax section will disappear, & the point of the piece is lost.

Years later, those same bells were chosen to play the Air (1987) in the minimalist soundtrack written for the James Broughton film The Scattered Remains of James Broughton. The Javanese style balungan melody was accompanied by harpsichord ostinato & percussion, and also subsequently re-orchestrated under the title “Air for the Poet.”

The Esperanto titled Serenado por Gitaro (1952) was Harrison’s first composition for refretted guitar. Written in a letter to his friend and colleague Frank Wigglesworth,

it contained this instruction: Anyone who just might own a guitar with movable frets should arrange these to play the “Intense Diatonic” (Syntonon Diatonic), which is the ‘vocal’ major scale. The piece will sound lovely in that tuning. He wasn’t able to hear the piece correctly tuned until the nylon-strung “Guitar with interchangeable fingerboards” was invented 25 years later, but eventually preferred it on the re-fretted National.

While the charming Music for Bill & Me (1967) was composed for Harrison and his partner William Colvig to play as a duo on their newly acquired troubadour harp, the concluding JAHLA in the form of a ductia to pleasure Leopold Stokowski on his ninetieth birthday (1972) was also written for two players: harp & percussion. In this recording, however, it is presented without the original percussion ostinato of finger cymbals and tambourine jangles, in the manner of the opening jahla of the composer’s Serenade for Guitar (1978). — J.S.

In Memoriam: Don Young, National Resophonic Guitars

Tunings

1-3 Scenes from Nek Chand

| 1/1 | 7/6 | 4/3 | 3/2 | 8/5 | 11/6 | 2/1 |

| D | F | G | A | B | C# | D |

| 0 | -33 | -2 | +2 | -16 | -51 | 0 |

4-7 Tombo por Lou

| 1/1 | 28/27 | 9/8 | 7/6 | 5/4 | 4/3 | 11/8 | 3/2 | 14/9 | 5/3 | 7/4 | 11/6 | 2/1 |

| D | Eb | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | Bb | B | C | C# | D |

| 0 | -37 | +4 | -33 | -14 | -2 | -49 | +2 | -35 | -16 | -31 | -51 | 0 |

8 The Day Before

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 7/6 | 5/4 | 4/3 | 3/2 | 5/3 | 7/4 | 2/1 |

| D | E | F | F# | G | A | B | C | D |

| 0 | +4 | -33 | -14 | -2 | +2 | -16 | -31 | 0 |

9-10 Quando Cosas Malas Malas Caen del Cielo

| 1/1 | 28/27 | 9/8 | 7/6 | 5/4 | 4/3 | 11/8 | 3/2 | 17/9 | 5/3 | 7/4 | 11/6 | 2/1 |

| D | Eb | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | Bb | B | C | C# | D |

| 0 | -37 | +4 | -33 | -14 | -1 | -49 | +2 | -35 | -16 | -31 | -51 | 0 |

11 Man’s Best Friend

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 7/6 | 5/4 | 4/3 | 11/8 | 3/2 | 5/3 | 7/4 | 2/1 |

| D | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | B | C | D |

| 0 | +4 | -33 | -14 | -2 | -49 | +2 | -16 | -31 | 0 |

12-18 Rational Melodies

| 1/1 | 5/4 | 3/2 | 5/3 | 2/1 |

| D | F# | A | B | D |

| 0 | -14 | +2 | -16 | 0 |

| 1/1 | 10/9 | 7/6 | 4/3 | 112/81 | 14/9 | 5/3 | 11/6 | 2/1 |

| A | B | C | D | Eb | F | Gb | Ab | D |

| 0 | -18 | -33 | -2 | -39 | -35 | *16 | *51 | 0 |

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 9/7 | 81/56 | 45/28 |

| Eb | F | G | A | B |

| 0 | +4 | +35 | +39 | +21 |

| 1/1 | 8/7 | 32/27 | 4/3 | 32/31 | 16/9 | 2/1 |

| C | D | Eb | F | G | Bb | C |

| 0 | +31 | -6 | -2 | +29 | -4 | 0 |

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 7/6 | 5/4 | 21/16 | 3/2 | 14/9 | 27/16 | 7/4 | 2/1 |

| G | A | Bb | B | C | D | Eb | E | F | G |

| 0 | +4 | -33 | -14 | -29 | +2 | -35 | +6 | -31 | 0 |

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 7/6 | 4/3 | 3/2 |

| D | E | F | G | A |

| 0 | +4 | -33 | -2 | +2 |

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 7/6 | 4/3 | 3/2 | 7/4 | 2/1 |

| D | E | F | G | A | C | D |

| 0 | +4 | -33 | -2 | +2 | -31 | 0 |

19 17-23

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 7/6 | 5/4 | 4/3 | 3/2 | 5/3 | 7/4 | 11/6 | 2/1 |

| D | E | F | F# | G | A | B | C | C# | D |

| 0 | +4 | -33 | -14 | -2 | +2 | -16 | -31 | -51 | 0 |

20 Almost Square

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 7/6 | 4/3 | 3/2 | 5/3 | 7/4 | 2/1 |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | A |

| 0 | +4 | -33 | -2 | +3 | -16 | -31 | 0 |

21 Is Is

(Low) D—G—D—G—A—D (High)

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 7/6 | 5/4 | 21/16 | 3/2 | 14/9 | 27/16 | 7/4 | 2/1 |

| G | A | Bb | B | C | D | Eb | E | F | G |

| 0 | +4 | -33 | -14 | -29 | +2 | -35 | +6 | -31 | 0 |

22-27 Suite for National Guitar

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 21/16 | 3/2 | 14/9 | 7/4 | 2/1 |

| G | A | C | D | Eb | F | G |

| 0 | +4 | -29 | +2 | -35 | -31 | 0 |

| 1/1 | 6/5 | 27/20 | 3/2 | 9/5 | 2/1 |

| B | D | E | F# | A | B |

| 0 | +16 | +20 | +2 | +18 | 0 |

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 4/3 | 3/2 | 5/3 | 7/4 | 1/1 |

| D | E | G | A | B | C | D |

| 0 | +4 | -2 | +2 | -16 | -31 | 0 |

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 5/4 | 21/16 | 3/2 | 5/3 | 15/8 | 2/1 |

| G | A | B | C | D | E | F# | G |

| 0 | +4 | -14 | -29 | +2 | -16 | -31 | 0 |

| 1/1 | 10/9 | 32/27 | 4/3 | 40/27 | 16/9 | 2/1 |

| E | F# | G | A | B | D | E |

| 0 | -18 | -6 | -2 | -20 | -4 | 0 |

| 1/1 | 9/8 | 5/4 | 21/16 | 3/2 | 5/3 | 15/8 | 2/1 |

| G | A | B | C | D | E | F# | G |

| 0 | +4 | -14 | -29 | +2 | -16 | -31 | 0 |

Just National Guitar

Producer: John Schneider

Recording Engineer & Editing: John Schneider

Mastering: Scott Fraser Architecture

Liner Notes: John Schneider

Art Direction: Erin Schneider

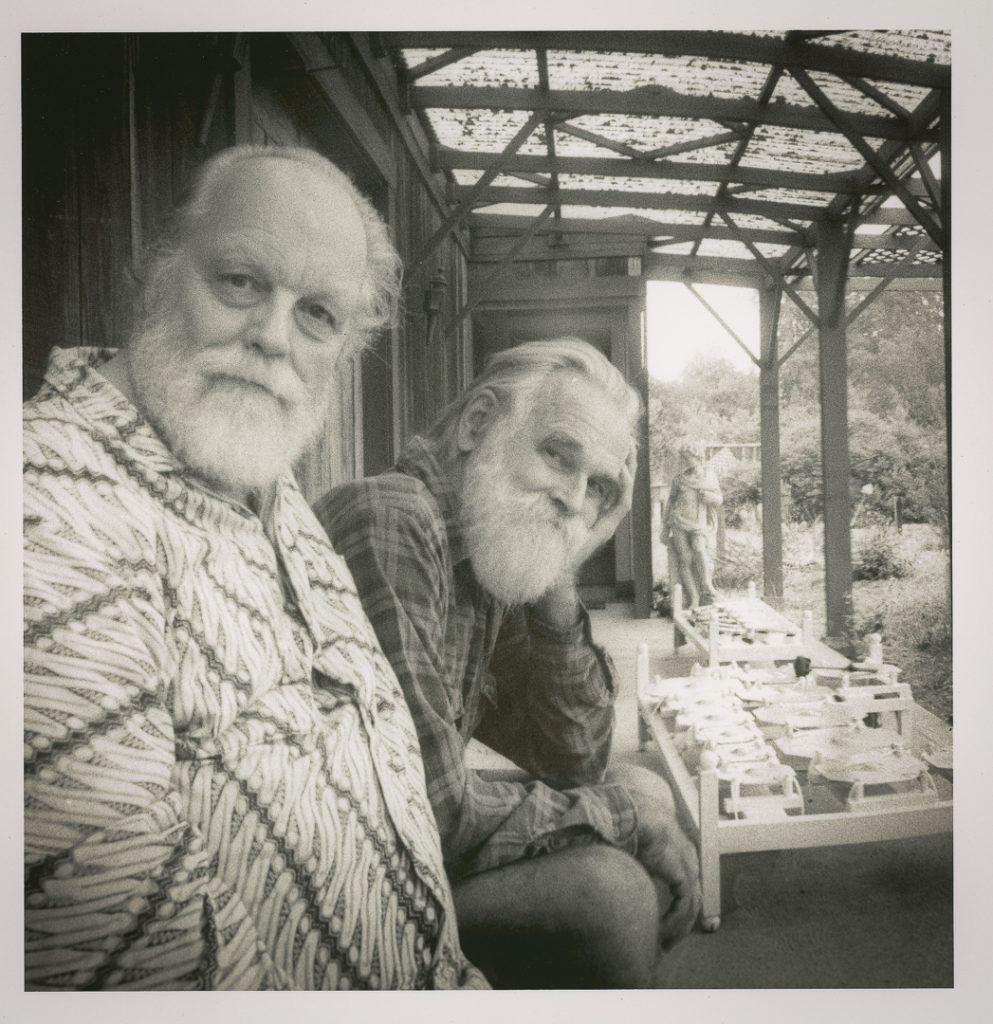

Photographs: Lou Harrison — by John Schneider

National Guitar — by Felix Salazar, Guitar Salon International

Nek Chand’s Rock Garden — Raw Vision, used by permission

Lou Harrison & Bill Colvig — by Dennis Keely

Recording Dates: all compositions recorded at The Library, Venice CA

Scenes from Nek Chand – July, 2013

Tombo por Lou – April, 2013

Quando Cosas Malas caen del Cielo – January, 2014

Quips – March, 2017

Rational Melodies – November, 2016

Almost Square – January, 2015

Suite for National Steel – October, 2016

Publishers

Harrison: Scenes from Nek Chand & Jahla — Frog Peak Music

Solo & Air — Hermes Beard Press

Serenado, Music for Bill & Me, Jahla in the form of a Ductia — Salvi Harp Corporation

Schneider: ms.

Riley: AMP Associated Music Publishers, Inc.

Yates: ms.

Johnson: Editons 75, Paris

Scholz: ms.

M•F 12

℗©2019 MicroFest Records, all rights reserved