10000 Things – Notes

Track List

USB I-Ching Edition

1 Quintet

45’ for speaker, string player, percussionist, & two pianists

5 Quartets

45’ for speaker, string player, percussionist, & pianist [34′]

45’ for speaker, string player, percussionist, & pianist [31′]

45’ for speaker, string player, & two pianists

45’ for speaker, percussionist, & two pianists

34′ 46.776” for string player, percussionist & two pianists

10 Trios

45’ for speaker, string player, & percussionist ~ 45’ for speaker, string player, & pianist [34′]

45’ for speaker, string player, & pianist [31′] ~ 45’ for speaker, percussionist, & pianist [34′]

45’ for speaker, percussionist, & pianist [31′] ~ 45’ for speaker, & two pianists

34′ 46.776” for string player, percussionist, & pianist [31′] ~ 34′ 46.776” for string player, & two pianists

34′ 46.776” for percussionist, & two pianists ~ 31′ 57.9864” for string player, percussionist, & pianist [34′]

10 Duos

45’ for speaker & string player ~ 45’ for speaker & percussionist

45’ for speaker & pianist [34′] ~ 45’ for speaker & pianist [31′]

34′ 46.776” for a pianist & string player ~ 34′ 46.776” for a pianist & percussionist

34′ 46.776” for two pianists ~ 31′ 57.9864” for a pianist & string player

27′ 10.554” for a percussionist & string player ~ 31′ 57.9864” for a pianist & percussionist

5 Solos

26′ 1.1499” for a string player (1955)

45′ for a Speaker (1954)

27′ 10.554” for a percussionist (1956)

31′ 57.9864” for a pianist (1954)

34′ 46.776” for a pianist (1954)

John Cage, narrator

Vicki Ray, prepared piano

Aron Kallay, prepared piano

Tom Peters, double bass

William Winant, percussion

The Ten Thousand Things

Though Cage’s midcentury masterpiece was never published under the above title, it was the term that he used in his notes when referring to his grand project, an open-ensemble piece that was to be, “a large work which will always be in progress and will never be finished; at the same time any part of it will be able to be performed once I have begun. It will include tape and any other time actions, not excluding violins and whatever else I put my attention to…” [letter to Pierre Boulez, 1953]. Both the macro & micro structure of the work was to be based on 13 parts with the proportions 3, 7, 2, 5, 11, 14, 7, 6, 1, 15, 11, 3, 15. As Cage reminds us in 45” for a Speaker,

It just happened that the series of numbers which are at the basis of this work add up to 100 x 100 which is 10,000. That is pleasing, momentarily: The world, the 10,000 things.

Pleasing indeed, as the number 10,000 is immediately recognizable to readers of both Taoist & Buddhist literature as the poetic reference to the infinite – the magnificent, uncountable diversity of Heaven and Earth. This was deeply resonant for the composer, who was not only actively seeking new ways to create a multiplicity of materials, but had also famously opened the windows of the concert hall to welcome any and all sounds that the universe could provide in his “silent” composition 4’33”.

In The Ten Thousand Things, Cage succeeded in creating a work that met both of his proposed criteria. Sadly, his prediction was only too accurate in one regard – it was literally never finished, as the work for tape and a fragment for voice were never completed. But it has remained happily “always in progress,” producing many performances of the five completed works that have found their way onto recordings and concert stages worldwide. Perpetually in progress, too, because any and every performance is, by design, determined by unique choices – of pitch, volume, duration, instruments – for which every moment will never be the same twice, just like life itself.

What inspired this recording was the recent discovery of a long lost 1962 recording of the composer reading his 45’ for a Speaker, and the recent technical ability to present these five compositions in every conceivable combination, resulting in an infinitude of variations, as per the composer’s wishes.

While the CD presents just one of an infinite number of possible realizations, the special I Ching Edition enables the performance of any one of the (5) solo works alone; or if one chooses, any combination, also making possible (10) duos, (10) trios, (5) quartets, and (1) quintet. And each performance itself is recombinant, that is, the 28 sections of each composition are rearranged such that they are played back in a different order, while the spaces between the sections are also altered. That makes (31) completely different compositions: only the solo works retain their original form – all else changes.

Coins are then tossed. Form’s not the same twice.

Remember those proportions? As these are “duration pieces”, notated graphically with time measured in seconds, Cage indicated each of the requisite sections with vertical dotted lines, timed to an accuracy of one ten-thousandth of a second. For every new ensemble performance, the I Ching Player shuffles every section in each work [with the exception of 45’ for a speaker, which was also written to a timeline, but without dotted lines]. Any particular performance can also be instantly reshuffled by double-clicking the play button:

Any amount of this music may be played or not and in any combination (vertical or horizontal) with other parts written (for a pianist, for a string-player) or to be written. As a rule structural amounts (indicated by dotted vert. lines connecting the staves) will be performed alone or in such combinations.

The title of each specific combination is the length of the longest composition, followed by a description of the performers. Cage gives one such possibility as 34’ 46.776” for 2 pianists, string-player, dancer and magnetic tape operator, revealing the delicious possibility of these works being considered suitable for choreography.

34′ 46.776” for a pianist (1954) ~ 31′ 57.9864” for a pianist (1954)

Cage composed these two works for himself and David Tudor to play while on tour in Europe in 1954, the second being the more difficult of the two and written specifically for Tudor. Like all the works in The Ten Thousand Things, they share the structure of 28 units, each divided into 5 phrases, which are grouped in 5 sections with proportions [3, 7, 2, 5, 11]. These were his last works for prepared piano, but the first where both the preparations and their placement were left up to the discretion of the performer. Intriguingly, it was also the only time that he requested the performers to change preparations during a performance. Notes could be played on the strings themselves with fingers, mallets, and other items, while other sounds included noises made on the interior and exterior of the instrument, as well as the use of accessories such as whistles, vocal noises, percussion instruments, etc.

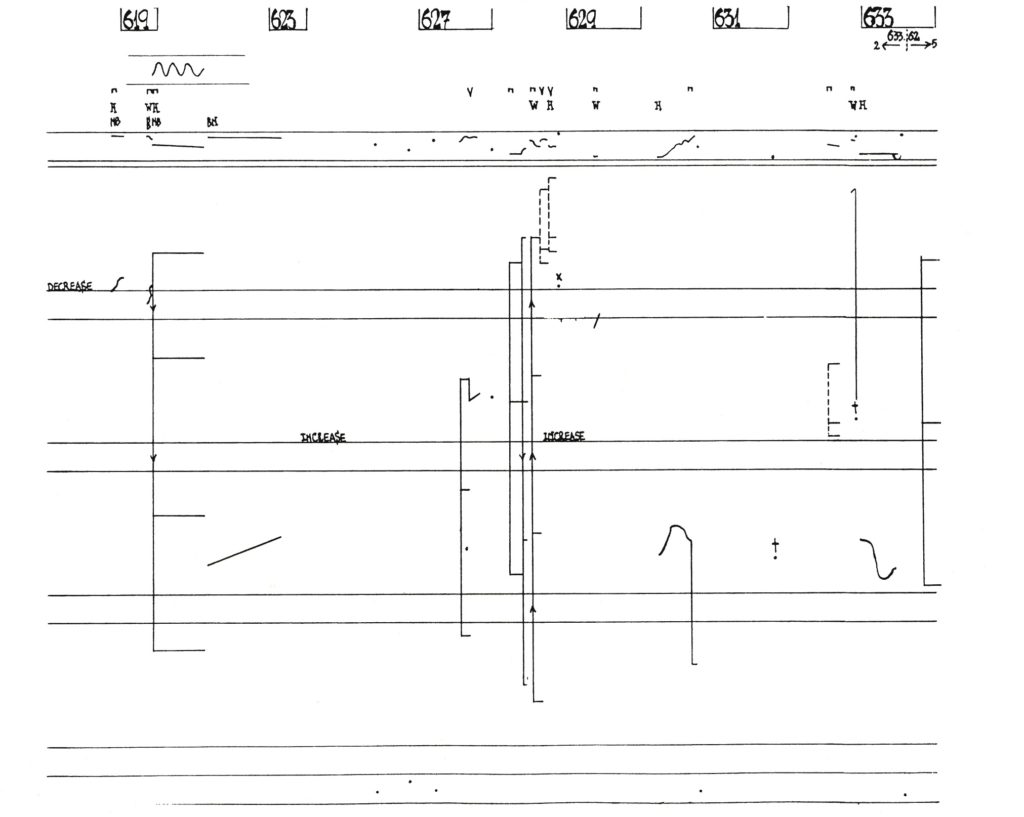

While the pitches to be played on the keyboard are notated using the standard grand staff, their dynamics are described in excruciating detail by indicating the manner of playing the keys, rather than their resulting volume. Above the staff, the series of three bands which indicate DEGREE OF FORCE (most to least), VERTICAL DISTANCE (far to close) and SPEED OF ATTACK (slow to fast) are peppered with tiny dots showing exactly how each note should be accomplished, with the added proviso, “Where impossibilities are notated (of any kind), the pianist is free to use his own discretion.”

45’ for a Speaker (1954)

Cage’s marvelously entertaining aesthetic manifesto was written immediately after the two prepared piano pieces and uses their exact same structure. In his introduction, also recorded here for the first time, he describes the process of selecting sections of old lectures, writing new ones, and determining the order of their presentation by chance operations.

The piano parts had included noises and whistles in addition to piano and prepared piano tones. For the speaker, I made a list of noises and gestures. By means of chance operations, determining which noise or gesture and when it was to be made, I added these to the text.

The speaker lights a match, combs his hair, slaps the table, leans his elbow on the table, etc., while the relative loudness the text is varied between soft, normal and loud, also I Ching determined. Some sections are read very quickly, some very slowly (with the narrative often jerking from one subject to another within a single sentence), instantly revealing the splicing technique used in all of the works, but made all the more obvious when applied to text.

26’ 1.1499” for a String Player (1955)

This work began as six short compositions (1953), none lasting much more than a minute, and specifically written for any bowed, four-stringed instrument. The notation is graphic, with four wide bands representing each string, and a completely separate band devoted to the activities of the bow. In more traditional music, the primary elements of melody and rhythm are typically determined by style or personal taste. Here, the individual parameters of each note ‘event’ (pitch, vibrato, bow position, pressure and material, glissandi, etc.) were determined separately by throwing I Ching coins, resulting in often wildly disparate actions happening in rapid succession, making the work literally impossible to perform as written. Cage surely realized this, since the directions also suggest that the part could be shared between two or more players, each responsible for a single string. Another band of notation is devoted to noises produced on the soundbox, and sounds not produced on the strings, which may also come from other sources such as percussion instruments, radio, whistles, etc.

In 1955, with the help of David Tudor, Cage added new sections to the original short string pieces, using the same structure as the two prepared piano pieces, bringing the final duration closer to its current value. While 59 1/2” for a string player was not included in the final published version of the work, it is incorporated in this recording.

27’ 10.554” for a percussionist (1956)

This last score of The Ten Thousand Things uses the same structure as the string and piano pieces (28 units in 5 sections), and bears the distinction of being the first solo percussion work of the century. It is completely graphic in notation, with four lines, each devoted to M (metal), W (wood), S (skin), or A (all others, eg. electronic devices, mechanical devices, radios, whistles, etc.). Choice of instruments from each of these four categories is completely up to the performer, though Cage encourages a “virtuoso performance” to include “an exhaustive rather than conventional use of the instruments employed,” suggesting at least twelve ways of using a gong.

Rather than pitch, each staff line represents the volume mf, with three kinds of sound events notated with a point, a line, or a combination of both. The A line was realized with radio and electronic signals inspired by the composer’s earlier Williams Mix (1952).

How does the listener approach these works? Does the use of random choice render these sounds meaningless, as some cynics claim? Quite to the contrary – I would suggest that Cage’s erasure of the ego from the process of composition actually unleashes what he called the “divine unconscious”, which informs every moment of this music. Poetry abounds – each new pas de deux or pas de trois (etc.) reveals a fresh phrase, gesture, or timbre, creating an endless kaleidoscope of musical invention. Perhaps the composer himself gives us the best advice in 45’ for a Speaker:

So that listening one takes as a springboard the first sound that comes along; the first something springs us into nothing and out of that nothing arises the next something; etc. like an alternating current. Not one sound fears the silence that extinguishes it. But if you avoid it, that’s a pity, because it resembles life very closely & life and it are essentially a cause for joy.

– John Schneider

“John Cage’s Ten Thousand Things: ‘Music is an oversimplification of the situation we are actually in’”

Tao called Tao is not Tao.

Names can name no lasting name.

Nameless; the origin of heaven and earth

Naming: the mother of the ten thousand things.

—Lao-tzu, Tao Te Ching 1

All that is necessary is an empty space of time and letting it act in its magnetic way.

Time, which is the title of this piece (so many minutes, so many seconds), is what we and sounds happen in. Whether early or late: in it. It is not a question of counting.

The reason I am presently working with imperfections in paper is this: I am thus able to designate certain aspects of sound as though they were in a field, which of course they are.

To see one must go beyond imagination and for that one must stand absolutely still as though in the center of a leap.

Composers are spoken of as having ears for music, which generally means that nothing presented to their ears can be heard by them. Their ears are walled in with sounds of their own imagination.

Exerpt from 26’ 1.1499” for a String Player,

©1960 Henmar Press (used by permission)

Music is simply trying things out in school fashion to see what happens. Etudes. Making it easier but not real. Theater is the only thing that comes near what it is.

For instance, now, my focus involves very little: a lecture on music. But it is not a lecture, nor is it music; it is, of necessity, theatre: What else? If I chose as I do, music, I get theatre, that, that is, I get that too. Not just this, the two.

Giving up counterpoint one gets superimposition and, of course, a little counterpoint comes in of its own accord.

Unloose your mind and set your spirit free. Be still as if you had no soul. [Kwang-tse]

—David W. Bernstein

1 Lao-Tzu, Tao Te Ching, trans., Stephen Addiss and Stanley Lombardo (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 1993), 1. This elegant translation includes a brief, yet informative, description of the text by Burton Watson.

2 Idem, I-VI (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 26.

3 For a detailed account of the genesis of The Ten Thousand Things, see James W. Pritchett, “The Development of Chance Techniques in the Music of John Cage, 1950-1956,” Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1988, 237-310.

4 Ibid., 279. Following a practice initiated by David Tudor for his performance of the Music of Changes Cage, converted metric time (i.e., time according to beats) with changing tempi to clock time.

5 Idem, “45’ for a Speaker,” 149.

6 Cage, “Composition as Process,” in Silence, 36.

7 For a controversial reading of Cage’s reactions to cellist Charlotte Moorman’s famous (infamous) interpretations of 26’ 1.1499” for a String Player see Benjamin Piekut, Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and Its Limits (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011), 40-176.

8 Amy C. Beal, New Music, New Allies: Experimental Music in West Germany from Zero Hour to Unification (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006), 69-71.

According to Beal, the two musicians performed a complete version of 31’ 57.9864” for a Pianist and 34’ 46.776” for a Pianist after the formal concert concluded.

9 Ibid.

10 Michael Kirby and Richard Schechner, “An Interview with John Cage,” in Happenings and Other Acts, ed., Mariellen Sanford (London and New York: Routledge, 1995), 64.

11 Ibid., 51.

12 For the complete list see Cage “45’ for a Speaker,” in Silence, 146-48.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

Artists

John Cage was easily one of the most innovative and controversial composers of the 20th Century. A pioneer in percussion, electronic, and aleatoric music, his introduction to Buddhism in the 1950’s profoundly changed his musical direction, as did his use of the ancient Chinese oracle I Ching, which he used to erase his ego from the act of composition. His extraordinary imagination produced well over 300 pieces, though his boundless creativity often embraced the world of art, dance and literature as well.

Described as a “modern renaissance man,” (Over the Mountain Journal) Grammy® nominated pianist Aron Kallay‘s playing has been called “exquisite…every sound sounded considered, alive, worthy of our wonder” (LA Times). “Perhaps Los Angeles’ most versatile keyboardist,” (LaOpus) Aron has been praised as possessing “that special blend of intellect, emotion, and overt physicality that makes even the thorniest scores simply leap from the page into the listeners laps.” (KPFK) Aron’s performances often integrate technology, video, and alternate tunings; Fanfare magazine described him as “a multiple threat: a great pianist, brainy tech wizard, and visionary promoter of a new musical practice.”

Aron has performed throughout the United States and abroad and is a fixture on the Los Angeles new-music scene. He is the co-founder and board president of People Inside Electronics (PIE), a concert series dedicated to classical electroacoustic music, the managing director of MicroFest, Los Angeles’ annual festival of microtonal music, and the co-directer of the underground new-music concert series Tuesdays@MONK Space. He is also the co-director of MicroFest Records, whose first release, John Cage: The Ten Thousand Things, was nominated for a Grammy® award for Best Chamber Music Performance. Aron has recorded on MicroFest, Cold Blue, Delos, and Populist records. In addition to his solo work, Aron is currently a member of the Pierrot + percussion ensemble Brightwork newmusic, the Varied Trio, and the Ray-Kallay Duo. He is on the faculty of Pomona College and Chapman University.

Tom Peters is a composer, writer & performer. He has performed and toured internationally with Grammy® winning Southwest Chamber Music since 1998, and as a soloist with Ensemble Oh-Ton, People Inside Electronics, MicroFest, the Schindler House, Nordwest Radio (Hamburg) and many others. Tom specializes in creating music for silent films, performing original scores through looping electronics and synchronized electronic soundscapes. As a writer, his blogs Asperger’s Ukulele and The Aspie and the NT document life with Asperger’s Syndrome, a form of autism. Tom is on the faculty of the Bob Cole Conservatory of Music at the California State University, Long Beach, and has been a member of the Long Beach Symphony since 1993.

Described as “phenomenal and fearless”, pianist Vicki Ray has commissioned and premiered dozens of new works by today’s leading composers. She is a long time member of the award-winning California E.A.R. Unit, Xtet and a founding member of Piano Spheres. As the head of keyboard studies at the California Institute of the Arts she was recently named the first recipient of the Hal Blaine Chair in Musical Performance. Vicki has appeared on numerous international festivals and is a regular member of the faculty at the Bang On a Can Summer Festival at MASS MoCA. She performs regularly with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and has been featured on the Green Umbrella Series as soloist and collaborative artist. Her widely varied career covers the gamut of new and old music: from Boulez to Reich, Wadada Leo Smith to Beethoven. Notable recordings include the first Canadian disc of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire with the Blue Rider Ensemble, the premiere recordings of Steve Reich’s You Are (Variations) and the Daniel Variations with the Los Angeles Master Chorale and the first recording of Cages Europeras 3 and 4. New releases include Morton Feldman’s Piano and String Quartet with Eclipse Quartet on Bridge Records and David Rosenboom’s Twilight Language on Tzadik.

William Winant is “one of the best avant-garde percussionists working today” according to music critic Mark Swed (Los Angeles Times). He has performed with some of the most innovative and creative musicians of our time, including John Cage, Iannis Xenakis, Pierre Boulez, Frank Zappa, Keith Jarrett, Roscoe Mitchell, Anthony Braxton, Fred Frith, James Tenney, Terry Riley, Steve Reich and Musicians, Frederic Rzewski, Danny Elfman/Oingo Boingo, Sonic Youth, Yo-Yo Ma, and the Kronos String Quartet. He has made over 200 recordings, covering a wide variety of genres, and has premiered many new works written specifically for him, by such noted composers as John Cage, Christian Wolff, Lou Harrison, John Zorn, Peter Garland, Michael Byron, Paul Dresher, Alvin Curran, Chris Brown, David Rosenboom, Larry Polansky, Gordon Mumma, Alvin Lucier, Terry Riley, Fred Frith, Somei Satoh, and Wadada Leo Smith.